Herbals

Herbals are reference books that index plant cures. Sometimes, these encyclopedic volumes also give instruction on flower magic. Botanical remedies have been used around the world since pre-historic times. Evidence of written recipes and methods go back thousands of years.

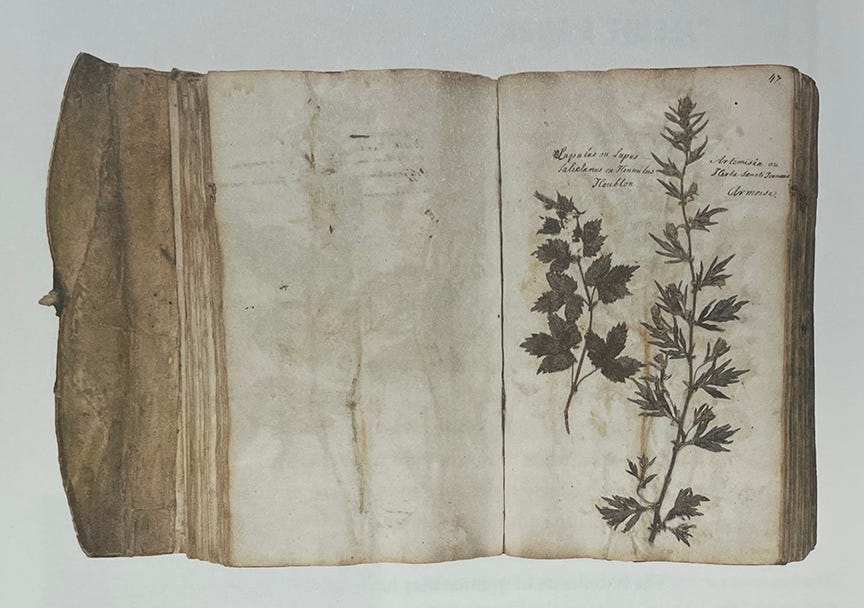

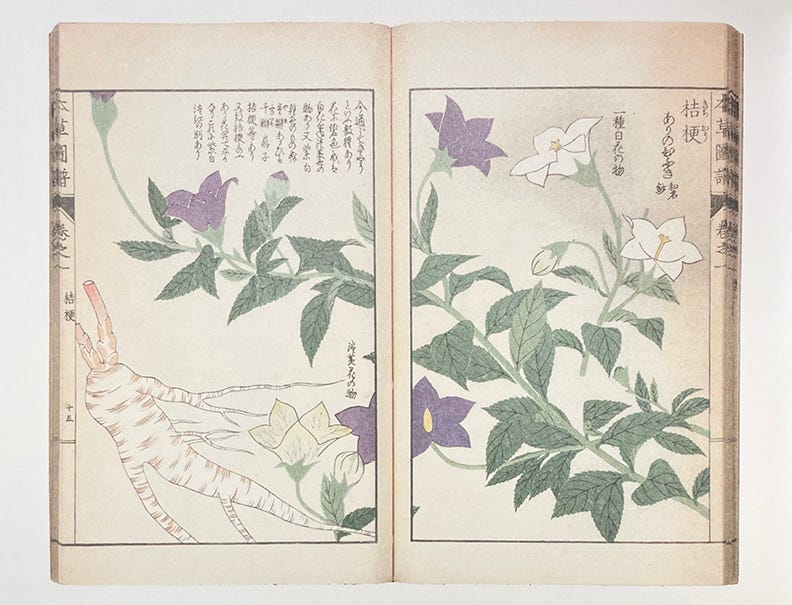

While visiting my friend, Kate Bolick, in New Haven, we stumbled upon an interesting exhibit: The Roots of Healing: Six Centuries of Medical Herbals, in the Sterling Memorial Library, at Yale University. Curated by Matthew Morrison M.D., the show includes a collection of notable books. Many of the iconic texts were familiar to me, but it was a delight to inspect the illustrations up close and in person. So much is lost when viewing a digitized image. I love the ruffled, edges of well worn pages that were bound together so long ago.

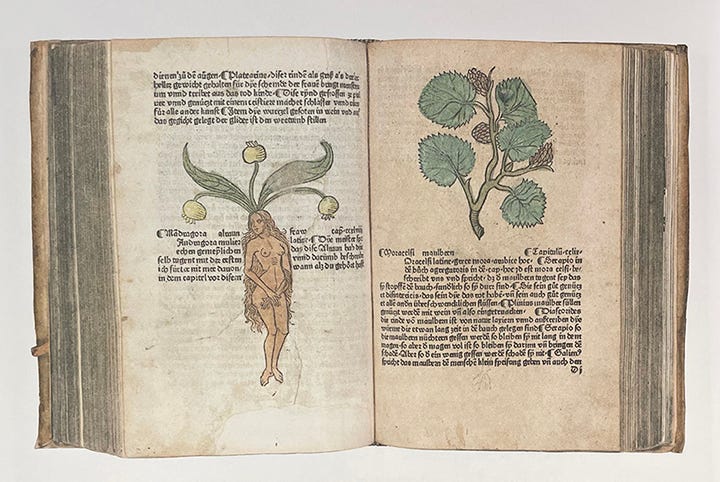

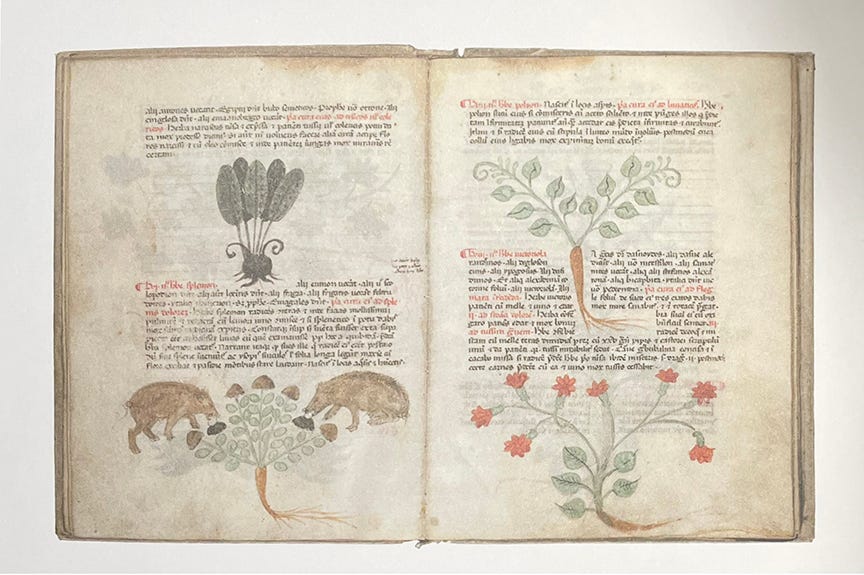

Many herbals from the late Medieval and early Renaissance eras anthologized classic ancient works with added illustrations. These manuscripts were most often kept by monks and priests in their abbeys. As practitioners of herbal medicine, they also tended to the gardens, growing the potent plants. Access to this type of information became more accessible after the printing press was introduced by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440.

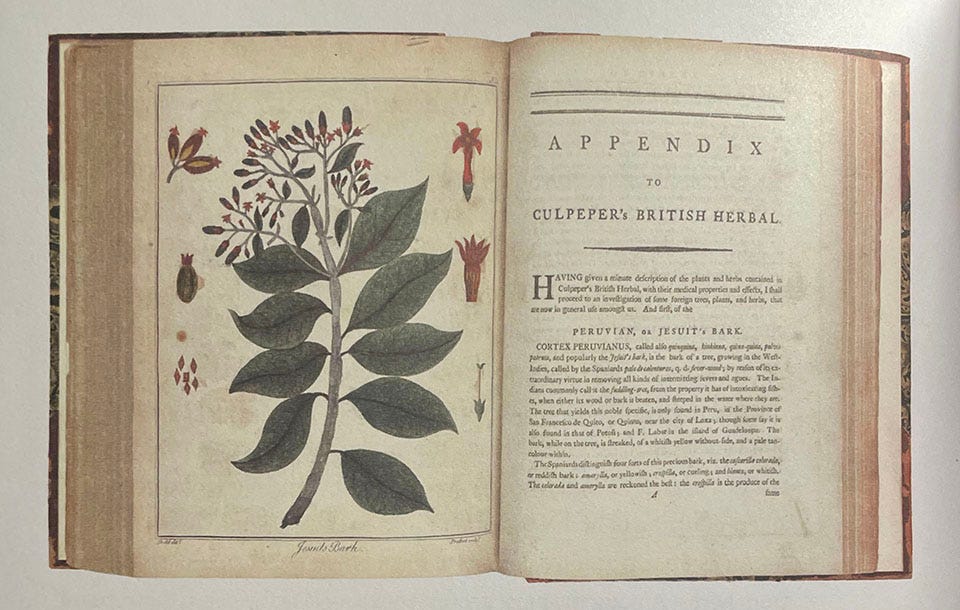

Seventeenth century Spanish Jesuit missionaries noticed the indigenous Quechua people of Peru using quinine from the Cinchona tree to treat fevers. The plant became known as “Jesuit’s Bark”. Quinine was used as an important treatment for malaria until the late 1920s. In the nineteenth century, British officers stationed in India started to consume quinine to prevent disease. Lime juice and gin were added to improve the bitter taste of the ‘tonic water’. A familiar concoction today, it is simply know as a gin & tonic.

Chinese biochemist, Tu Youyou looked to ancient Chinese herbals for clues. This research brought her to GE Hong’s Handbook of Prescriptions for Emergencies circa 317 - 420 CE which listed Artemisia annua (sweet wormwood) as a cure for quartan malaria. This led to Youyou’s Nobel Prize winning discovery of the anti-malarial compound, artemisinin, in 1972.

Pseudoscientific herbalism has always been, and continues to be a problem. This is why ethical, evidence based, studies are so important. It has been suggested that only five percent of the 250,000 known flowering species have been investigated for their medicinal potential.

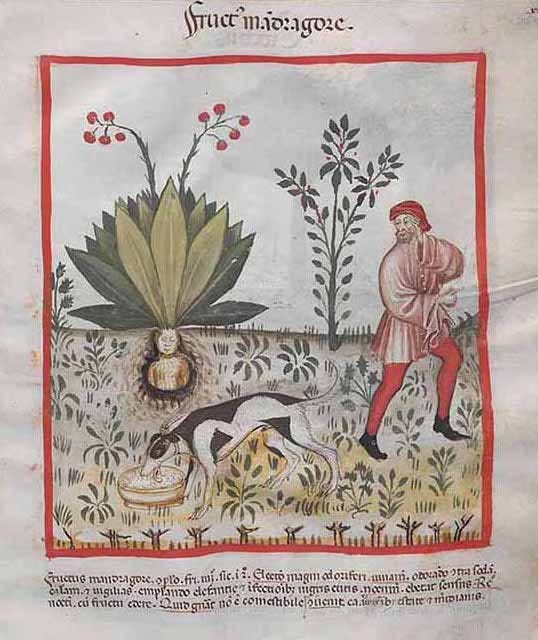

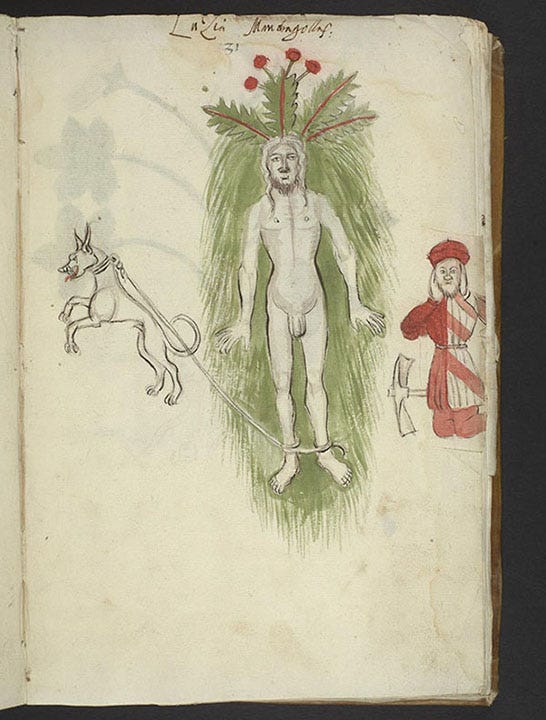

Mandragora

“the insane root / that takes the reason prisoner”

- from Shakespeare’s Macbeth

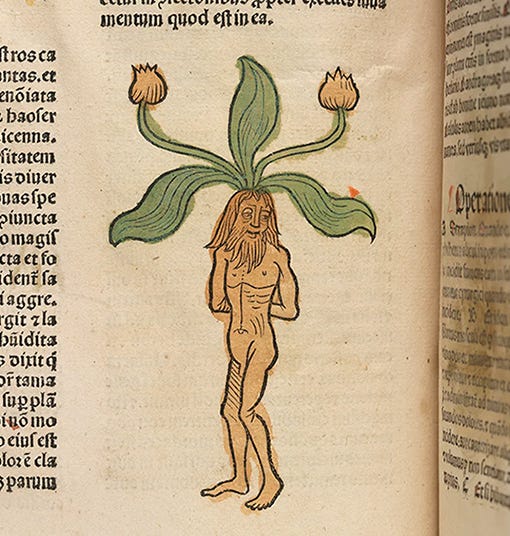

The Mandragora (mandrake) plant has hallucinogenic, hypnotic, and poisonous properties. A long time ago, it was used as an anesthetic before surgery.

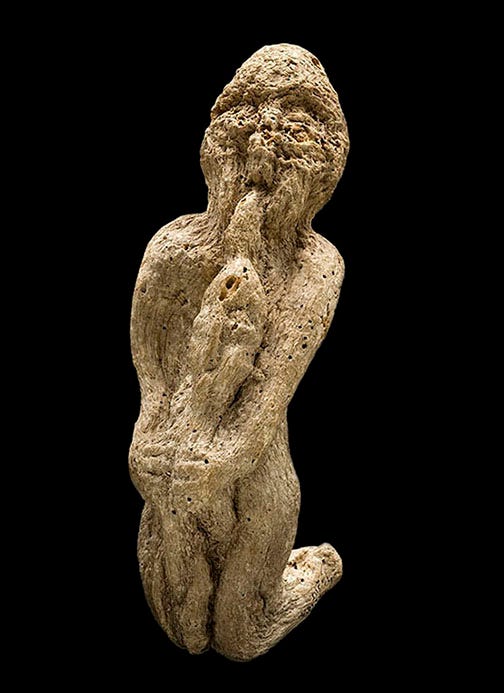

Mandrake roots have long been linked to magical lore due to their humanoid form. They are the subject of countless amusing illustrations. Superstition states that when pulled from the ground, the personified root shrieks so loudly that anyone within earshot will be killed from the sound. It was believed that the safest extraction method was to tie a dog to the plant, and in time the sacrificed dog would run off, pulling the root from the soil.

Mandrake has been used for love potions since ancient times. Dried and carved, the roots have also been used as a protective amulet.

What’s Left in the Remaking

What’s Left in the Remaking is a group exhibition and fundraiser that brings together works by NYC-based alumni artists and mentors who have shaped and been shaped by CUE Art Foundation’s exhibition program. My first NYC solo show, Wading Under a Crackling Sky, was curated by Glenn Ligon at CUE Art Foundation in 2007.

Featuring work by:

Golnar Adili, Karen Azoulay, Tsohil Bhatia, Tania Bruguera, Papuna Dabrundashvili, Robert Davis, Abigail DeVille, Zachary Fabri, Ernst Fischer, Fereidoun Ghaffari, Camilo Godoy, Juan Eduardo Gómez, David Humphrey, Steffani Jemison, Miatta Kawinzi, Devin Kenny, Myeongsoo Kim, Mo Kong, Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo, Athena LaTocha, Levani, Judy Linn, Yang Mai, Keli Safia Maksud, Esperanza Mayobre, Paul Miller (DJ Spooky), Naeem Mohaiemen, Shellyne Rodriguez, Cal Siegel, Kiki Smith, Catalina Tuca, James Yakimicki

CUE: 137 West 25th Street, New York, NY - on view until December 20, 2025